Julien Dupré essay

jlw

I. Setting the

Stage

Writing to his brother Theo from The Hague on a Sunday afternoon in December, Vincent van Gogh expressed his enthusiasm for a painter whose work had captured his attention. "Do you know whose work has made a deep impression on me? I saw reproductions of Juilen Dupré. One was of two reapers, the other, a splendid large woodcut from Monde illustré, of a peasant woman taking a cow into the meadow. It seemed to me outstanding, very energetic and very true to life."[1] Although the exact identity of these two paintings is uncertain, van Gogh's admiration of Dupré's work illuminates a theme that permeates European art during the second half of the nineteenth century-rural life and the work of agricultural laborers.[2]

This theme has its roots in the genre paintings of sixteenth century Dutch and Flemish artists such as Pieter Bruegel (1525-1569), but it is not until the middle of the nineteenth century that it emerges as part of the Realist challenge to the French academic tradition that customarily categorized such imagery as being of less importance than history painting, religious painting and portraiture. The painters who lived near the village of Barbizon were among the first to declare rural imagery worthy of serious consideration at the Salon; and although they did not have much success persuading the Salon juries to share their perspective, they did attract the attention of colleagues in other parts of Europe.[3]

Fueling the Barbizon painters' advocacy for rural subject matter was a growing concern about the destruction of the natural environment in the wake of industrialization. Not only was the countryside being carved up by railway lines and steam-powered factories, but the need for vast quantities of natural resources resulted in deforestation, in the creation of unhealthy and unsafe mining practices, and above all, in the denigration of the people who worked under these conditions. Further, as people increasingly sought factory jobs in the city, the countryside saw a significant population decline. These social and economic developments disrupted the agricultural rhythms that had been the foundation of life for centuries.

The aesthetic response to these new social and economic conditions was both stylistic and political.The Revolution of 1830 in France prompted an interest in depicting the daily life of ordinary people, often in the context of the social issues of the time. The influx of people seeking work in the new industrial economy of Paris resulted in new pressures on both social service providers and the city's infrastructure. The effect was all too predictable-poverty, unemployment and illness.

The arts community reacted in many ways. Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) worked for La Caricature and later Le Charivari, both journals established by Charles Philipon in the1830s, where he created satirical images lampooning the corrupt and incompetent government as well as self-important public figures. The painter Philippe-Auguste Jeanron (1809-1877) expressed his dismay through canvases depicting the plight of destitute families. In the painting Scene de Paris (1833), the poverty-stricken family of a war veteran sits huddled against the quayside wall while well-dressed Parisians stroll past without a glance. (fig. 1)

fig. 1:

Philippe-Auguste Jeanron, Scene de Paris, 1833. Oil on canvas. Musée de Chartres,

Chartres, France. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/in-

dex.php?curid=14683723

The artist's traditional training is evident in the composition and the handling of space as well as figures, but the subject matter represents something quite different from earlier genre paintings. These figures are not amusing peasants, nor do they offer a picturesque glimpse of a Dutch kitchen or a French sitting room. Rather, this is a contemporary Parisian family whose father served in the military, but whose fortunes are dismal; they are hungry, tired and ill.

Although Romantic painters often expressed political views unapologetically, Daumier and Jeanron were among the earliest artists to reveal their social concerns without the mediation of literary, allegorical or historical iconography.[4] Similarly, the art critic Gabriel Laviron (1806-1849) was one of the first to call for an art that focused on the contemporary life of Paris, renouncing the coded allegories of the academy in favor of a more unvarnished portrayal of real people and activities in his commentary on the Salon of 1833. "Art does not consist of making trompe-l'oeil [imagery] but also of creating the specific character of each thing that one wants to depict. To do that, one must see and understand, so to speak, that it is necessary to have a spirit strong enough to grasp the characteristic differences that are in nature, and what is perhaps even more rare, the audacity to show them in all their truth."[5] By the end of the 1830s, a new aesthetic based on contemporary life had emerged. Although not yet labeled as Realists, these artists accepted the traditional techniques of painting while simultaneously rejecting the conventions of conveying meaning primarily through classical allusions and historical references.

By the time that Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) arrived in Paris in 1839, the core principles of the Realist movement were already in place, but the young painter from Ornans would soon make his presence known. He spent hours copying sixteenth and seventeenth century masters in museums, and in 1844 he began to exhibit at the Salon. Courbet gradually developed friendships with the art critics and writers Charles Baudelaire, Max Buchon and Champfleury as well as the painters François Bonvin, Armand Gautier and Jean Gigoux. The group often gathered at the Brasserie Andler on the rue Hautefeuille to ponder the definition of Realism while consuming what was then a new addition to the menu of Parisian cafes-beer.[6]

These discussions would be interrupted with the outbreak of revolution in February 1848. The corruption of Louis-Philippe's government had become intolerable, and the disenfranchisement of working and middle class citizens resulted in deepening support for reform. Because the government prohibited public demonstrations, the leaders of the reform movement implemented a strategy of hosting large banquets suitable for both fundraising and discussions of the issues. When the government outlawed the banquets in February 1848, Parisians took to the streets.

One witness to these events was the English journalist, Percy Bolingbroke St. John (1821-1889) who described the view from his window on February 22, 1848.

At this very time [about three], having returned to my residence to write a letter, I

was witness to a scene, which described minutely, may give an idea of many similar events. My residence is situated in the Rue St. Honore.... Called to my window by a noise, I saw several persons standing at the horses' heads of an omnibus. The driver whipped, and tried to drive on. The people insisted. At length, several policemen in plain clothes interfered, and as the party of the people was small, disengaged the omnibus, ordered the passengers to get out, and sent the vehicle home amid the hootings of the mob. A few minutes later, a cart full of stones and gravel came up. A number of boys seized it, undid the harness, and it was placed instantly in the middle of the street, amid loud cheering. A brewer's dray and hackney cab were in brief space of time added, and the barricade was made. The passers-by continued to move along with the most perfect indifference....[7]

The revolution was quickly concluded on February 23 when Prime Minister Guizot resigned and King Louis-Philippe fled to England in disguise. A provisional government was formed under the presidency of the poet Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-1869). The Second Republic was declared on February 26; universal male suffrage was proclaimed on March 2; and elections were scheduled for April 23. By June conflict between the progressive and conservative wings of the new government ignited another revolt by the working class citizens of Paris. Barricades were again erected in the streets and the army and national guard were called out to extinguish the uprising. (fig. 2) Ultimately, the conservatives won with the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in December, 1848. Almost exactly three years later, Louis-Napoléon staged a coup d'état and dissolved the National Assembly, thus initiating the Second Empire.

fig. 2: Thibault,

(1830-1927), Barricades

rue Saint-Maur. Avant l'attaque, 25 juin 1848. Daguerréotype. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Public Domain. https://www.histoire-image.org/fr/etudes/ ere

barricades-1827-1851?i=549&d=1&v=1848&w=1848&id_sel=941

See also the image of

the same location after the attack at L'Histoire par l'image: https://www.photo.rm-

n.fr/archive/02-010879-2C6NU0GP8OD2.html

Despite the social and political tumult of the Second Republic, it provided a welcome respite from entrenched academic juries favoring the status quo in art. The Salon of 1848, which opened a scant fortnight after the revolution, was open to all artists. There were no juries. Understandably, it was somewhat disorganized and overwhelming, but it did presage a more open-minded attitude toward the annual selection process. The following year, the Salon featured a variety of painters who would be identified with the Realist movement, including Rosa Bonheur, François Bonvin, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau. Above all, this Salon signaled that Realist art was increasingly accepted among the Paris arts community.

The Salons of 1850-51 were combined, opening officially on December 30, 1850 but not to the general public until January 3, 1851. This Salon was dominated by several controversial contributions, including Courbet's The Burial at Ornans and The Stonebreakers, as well as the equally problematic painting by Millet, The Sower. These canvases challenged public notions about rural life, provoking discomfort among viewers and critics alike. The Burial at Ornans depicted a funeral service attended by villagers who bear many signs of fundamentally unattractive human frailty and suffering; and The Stonebreakers and The Sower reminded viewers that these anonymous laborers engaged in onerous work to ensure the survival and comfort of bourgeois Parisians. They break stones to pave carriage roads and sow seeds to provide food for the dinner tables of the comfortable classes. The political point-with its attendant implication that thoughts of revolution were never out of the question-would have been clear to the Salon audiences of 1851.

Equally troublesome to the art critics was the representation of peasants and laborers as heroic figures deserving of the same respect as those typically portrayed in history paintings. Nonetheless, Théophile Gautier (1811-1872), one of the leading art critics of the time wrote in La Presse that The Sower was the most powerful representation of peasantry at the Salon, noting that "...he is bony, gaunt and scrawny under his livery of misery, and yet life pours forth from his large hand, and with a superb gesture, he who has nothing, scatters on the earth the bread of the future."[8]

Gautier was a consistent advocate for Realism and artistic independence: "One is in error, in our opinion, to affect a positive repugnance or rather a positive disdain for purely contemporary figures. We believe, for our part, that there are new effects, unexpected possibilities in the intelligent and honest representation of what we term modernity."[9] In short, contemporary life in all its myriad permutations was entirely legitimate as a subject for serious art. By the time the Salon closed on March 6, 1951, the Realist painters were acknowledged as important avant-garde contributors to the Parisian cultural environment.

Julien Dupré: Early years and education

Twelve days later, a child was born just a few miles away to Pauline Célinie Bouillié (1830-1885) and Jean-Marie-Pierre Dupré (1809-1904). Julien Dupré arrived on March 18, 1851 and was baptized on March 20 at the parish church of Saint-Jean-Saint-François.[10] The family included a half-brother, Jean-Marie-Pierre, who was sixteen years old when Julien was born.[11] In 1852, Pauline gave birth to a second child, Julie.

The Dupré family lived at the 11, rue des Enfants Rouges in the Marais quarter of Paris, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city.[12] In Dupré's time, it was a place of stark contrasts. Elegant eighteenth-century townhouses opened onto filth-laden medieval lanes. The extraordinary Place des Vosges, built by Henri IV between 1605 and 1612, was less than a mile from the ruins of the Bastille where the French Revolution had been ignited. In the post-Napoleonic era, the streets of the Marais were crowded with rural laborers seeking work in the factories of industrial Paris, creating a demand for housing that led to increasingly crowded conditions. The Dupré home was located near the original complex built by the Knights Templar, who received the property from Louis VII in 1137. Their first task was to drain the swampy area-le marais-before beginning the construction of their monastery. Over the next six centuries, the site underwent several transformations, including the development of the baroque Hôtel de Soubise beginning in 1708; today the building and courtyard comprise the Musée des Archives Nationales. As a child, Julien Dupré would have seen these large and elegant structures as well as the overcrowded conditions of the poor on a daily basis.

Dupré' father Jean worked as a jeweler, creating both fine jewelry and costume jewelry.[13] His older brother Jean also became a jeweler, and both his sister Julie and his niece Jeanne Henriette married jewelers.[14] In fact, Julien was the only child who did not follow this career. Instead, he was apprenticed to a lace-maker in the late 1860s. There he would have learned to trace patterns and perhaps create simple designs as well. The advent of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, however, forced the lace-maker's shop to close and Dupré soon found himself a soldier.[15]

After the cessation of overt hostilities with Prussia and the subsequent civil war of the Commune, Julien Dupré began his formal study of art. In 1872, he enrolled in a sketching class taught by Monsieur Laporte at the École des arts décoratifs in preparation for applying to the École des Beaux-Arts.[16] Once he was accepted, he entered the studio of Isidore Pils (1813-1875) and after Pils' death in 1875, the studio of Henri Lehman (1814-1882). It was also there that he met Georges Laugée (1853-1937), who would become a lifelong friend.

One of Dupré's early sketchbooks reveals the traditional course of study at the École des Beaux-Arts; it is filled with figures and animals as well as preliminary ideas for compositions, and drawings based on paintings by French baroque masters such as Laurent de La Hyre (1606-1656) and Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665). In his drawing after Poussin's Triumph of Flora (1627), Dupré has chosen to examine the figure of the water nymph Clytie, who anchors the right foreground of the painting. (figs. 3, 4) On bended knee, she reaches for the fragrant heliotrope in the grass, a flower that will become symbolic of her own transformation as a result of her unrequited love for the sun god Helios.[17] From Dupré's perspective this figure offered him an opportunity to study Poussin's technique of representing both the human figure and the complex folds of drapery created by Clytie as she leans forward to grasp the flower.

fig. 3: Etude d'apres Poussin, Pencil with watercolor highlighting 1873.

fig. 4: Nicolas

Poussin, The Triumph of Flora, 1627. Oil on canvas. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Dupré's art education at the École was supplemented by study with the academic painter and muralist Désiré François Laugée (1823-1896), the father of his friend Georges Laugée. The Laugée family was based in Nauroy, near Saint-Quentin in Picardy, where Dupré probably first met them on a visit with Georges. By the mid 1870s, however, the two young men were painting side by side while Dupré also studied with the elder Laugée. Like the younger artists Désiré Laugée had attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and by the 1870s, had a well established Salon career as a painter of religious subjects and portraits; he was also a prolific muralist, implementing large decorative programs for at least four churches.[18] By the time that Dupré met him, D. Laugée had also begun to depict scenes of the countryside surrounding his home, albeit with a degree of formality and elegance that belies the nature of rural life. He

undoubtedly encouraged his students to explore the emerging naturalist trend among artists such as Jules Breton and Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose work focused primarily on rural scenes of ordinary people.

By 1875, Dupré made two particularly significant decisions: he prepared for his Salon debut and he proposed marriage to Marie Eléonore Françoise Laugée (1851-1937), Georges' sister. Like her siblings, Marie was educated as an artist in her father's studio where she worked alongside the other young painters studying there. Her knowledge of the art world comes through clearly in her letter of April 4, 1876 to her aunt and uncle, Joachim and Caroline Malézieux. The letter begins with an invitation to her upcoming marriage, but quickly moves on to discuss her fiancé's imminent Salon debut.

If you have seen my aunt Nininne recently, you must know how successful Julien's painting was when it arrived here. More than forty people came to see it and everyone liked it very much, starting with the artists who were very happy with it. In short, it was a real and complete success since, the day after his [Dupré's] return, he found a collector who paid 3500ff for his painting. It was Mister Gallay, a friend of papa, who bought it and he is delighted with its acquisition; you understand that we are no less so than him; it's such a great start for a first year exhibitor. The day before yesterday, we learned that the painting received a good placement number. We can therefore now hope for a good place at the Salon where, undoubtedly, it will be noticed.[19]

Dupré's account books confirm this report in his first entry, which reads La Moisson en Picardie, (Harvest in Picardy) vendu a M. Gallay. 3500ff.[20] Not quite a month later, the painting appeared at annual Salon, which opened on May 1, 1876.

On May 17, 1876 Julien

Dupré married Marie Laugée in Nauroy, Picardy. They lived

with the bride's family both in Nauroy and at their home Passy near the Bois de

Boulogne in Paris.[21] The following spring Marie

gave birth to their first child, Thérese Marthe Françoise, on March 19, 1877.

The new father wrote a short, but excited note to his aunt and uncle Malézieux

announcing his daughter's arrival. "I'm happy to send you an announcement of

the birth of our daughter Thérese; she is a beautiful girl I

assure you. My beloved Marie is resting now, but she had a hard time. She asks

me to give you a hug; little Thérese also sends you kisses. Excuse

the brevity of this letter but I am a little overcome with emotion. Hug my

cousins for me. I embrace you with all my heart."[22]

Launching a

career

Dupré's successful

Salon debut in 1876 marked the beginning of a distinguished career. In May

1877, his work was again accepted by the Salon jury, and Fauchers de Seigle,

en Picardie (Rye Reapers in Picardy) was subsequently sold to a Mr. Wadsworth

of New York for 2500ff. Another canvas, Moissoneurs Buvant, (Harvesters

Drinking), was sold to a Mr. Turquet that year for 1000ff, bringing his total

income to 3500ff for the year. While not a fortune, this was a comfortable

income for a twenty-six year old artist.[23]

It was sufficient to establish a studio at 14 boulevard Flandrin with his

friend and brother-in-law Georges Laugée in 1878; the two men would share this studio for many years.

(fig.5)

fig. 5: Dupré's studio, 14 boulevard Flandrin, Paris

Another indication of Dupré's growing reputation was the coverage he received in the Gazette-des-Beaux-arts, one of the most prestigious of the Parisian art publications of the time. In his review of the Salon of 1878, Roger Ballu wrote: The Lieurs de Gerbes [Binding the Sheaves] by Mr. Julien Dupré is distinguished by natural attitudes and an excellent depth of color; there is perhaps a little monotony in the parallel movement of the two figures in the foreground.but one must recognize this robust and serious elevated art.[24] Shortly thereafter, the painting was purchased by the French government. In addition the well respected publishing house, A. Cadart Éditeur-Imprimeur, produced an etching of this painting for inclusion in an annual Salon album.

The

following year, Dupré received his first Salon jury recognition, an honorable

mention for Glaneuses (Gleaners). The year 1879 was also marked by a

dramatic increase in sales, including the painter's first forays into the

international market via the Knoedler Gallery, New York and Arthur Tooth &

Sons, London.[25] In Paris, Dupré's 1879

Salon painting La récolte des foins, Le regain (Second Harvest)

was purchased by Goupil & Cie where Théo van Gogh would soon take the reins as managing director.[26] His sales for 1879 totaled 9750ff, nearly

tripling his income from two years earlier and allowing him to provide a

comfortable life for his growing family.[27]

In the four years since his Salon debut, Dupré established his reputation as a notable young painter who

positioned his work within the Realist frame of reference established by the

generation of the 1830s.

II.

Building a Career

Dupré's generation came of age in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War when the Realism of the 1850s and 1860s was being enriched by trends converging from a variety of directions. Although there was occasionally fierce debate among individual artists, there was also a natural overlapping of diverse aesthetic perspectives during the Third Republic. The broad social context of the period was defined by increasing industrialization and internationalism as well as the often dramatic social consequences that followed.

One

of the most significant changes of the time was the opening of trade between

France and Japan in 1858. Western artists were introduced to aesthetic

conventions that were based neither on the mathematical perspective systems of

the Renaissance nor on classical and biblical cultural references. The impact

of Japanese design principles was evident as early as 1863 when Édouard Manet and James McNeill Whistler

made use of flattened spatial compositions in their controversial submissions

to the Salon des refusés. In

spite of the critical and public rejection of Luncheon on the Grass and Symphony

in White , No. 1: The White Girl, there was no doubt that Manet and

Whistler posed serious questions about the conventions of western art in these

canvases. A few years later, Whistler made his debt to Japanese art explicit in

Princess from Land of Porcelain (1864-65) as did Manet in his

Portrait of Zola (1868).[28] Their admiration of

Japanese art would be absorbed in turn by the slightly younger Realist painters

gathering in Paris in the 1860s.

In the opening years of the Third Republic, those artists would implement their plans for an independent exhibition that they had first proposed in 1867.[29] Inspired by the autonomous actions of both Manet and Courbet in organizing solo exhibitions to coincide with the Exposition universelle in 1867, and informed by their own experiences of erratic acceptance of their work by Salon juries, this group of young Realists opened their first independent show in 1874. Le Charivari's art critic Louis Leroy entitled his unfavorable review of the show "L'exposition des impressionistes", thus establishing the derogatory name by which the group soon became known.[30] Regardless of the initial public reception of their work, however, the Impressionists asserted the validity of independent exhibitions as an alternative to the annual Salons. They saw themselves as upholding the standards of the earlier Realists, both in depicting everyday life as their primary subject matter and in their willingness to experiment with new techniques, many of which were sparked by their exposure to Japanese art and design.[31]

Less experimental, but perhaps more influential in the short term was the Realism of painters like Isidore Pils (1815-1875), Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), and Alexandre Antigna (1817-1878). These men established their careers during the Second Empire under Napoleon III, but they drew a distinction between overt political commentary and the expression of compassion for the victims of social injustice. Composed and executed in the established Salon style, their paintings fostered an official acceptance of the social justice images by the French government. As Gabriel P. Weisberg has noted, "Realist art did not necessarily imply radical politics, but it did imply social consciousness."[32] The issues of poverty and inequity would continue to be represented throughout the Third Republic in the work of artists as diverse as Vincent van Gogh and Fernand Pelez.

For Julien Dupré, the most crucial inheritance from the earlier Realists was the development of a fresh approach to the painting of rural life, particularly the work of Jean-François Millet (1814-1875). There was a long tradition of depicting peasant life in the Holland and Flanders dating back at least as far as the 1400s, but the tone was typically comic, often with a moral lesson attached. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569) set the standard in sixteenth century Flanders, and was soon followed by the masters of the seventeenth century such as Adriaen Brouwer, Jan Steen, Gerard ter Borch and Pieter de Hooch. These artists specialized in domestic genre scenes that offered a glimpse of the daily life of the common people, whether sharing a meal at a humble table, tending cattle in the fields or cavorting at a local festivals. Like the earlier examples, these paintings too were frequently intended to provide social criticism of the mores of the time. Nineteenth-century Realism continued the tradition of social commentary, but generally eliminated the representation of rural workers as suitable subjects for derisive laughter. Courbet's painting of The Stonebreakers (1849) illustrates this new approach. In this work, an elderly man and a youth are shown breaking up stones by a countryside roadside; both wear ragged clothing and neither of their faces is visible to the viewer. These anonymous figures are neither comic nor pitiable. Rather, they represent a clear reminder to the bourgeoisie that their comfortable lives-including their smoothly paved carriageways-depend on workers who toil under oppressive conditions for minimal pay.

The

work of Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875) was equally controversial. His

transformation of the image of the rural French peasant into an iconic figure

deserving of respect found little acceptance during the Second Empire. At the

1857 Salon, The Gleaners provoked a contentious political discussion

about the traditional practice of gleaning. (fig.6)

fig. 6: Jean-François Millet, Gleaners, 1857. Oil on canvas. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Historically, rural communities were allowed to gather up the pieces of wheat left behind after harvesting the field. As grim as this might sound, it actually provided enough grain to be valuable to a poor family. For centuries, the practice was considered an act of charity approved by the church. As industrialized capitalism spread across France, however, landowners increasingly attempted to sell the right to glean rather than opening their fields to the local peasantry. Simon Kelly, curator of Millet and Modern Art From Van Gogh to Dalí, explains it in his essay "'This Artistic Fauve": Millet as Modern Artist". "With the context of this debate over the growing alienation of the gleaner within a capitalist economy, Millet represented three women with powerful curving and echoing forms that highlighted and ennobled their stoic labor. Conservatives saw a threatening message in Millet's sympathetic representation of these impoverished outsiders. The journalist Jean Rousseau thought the work incited revolution and that it recalled 'the pikes and scaffolds of 1783'."[33] In contrast, republican art critics viewed the painting as an expression of the nobility of downtrodden workers in the face of demoralizing poverty. With relentless consistency, the 1859 Salon jury rejected Millet's entry Death and the Woodcutter, a painting inspired by one of La Fontaine's fables, on the grounds that the woodcutter was a potentially insurgent figure who might be understood as a threat to the established order.[34]

His most infamous painting appeared at the 1863 Salon. Man with a Hoe was far more challenging than The Gleaners with its unapologetic depiction of a plain and weary man leaning awkwardly on his hoe as he rests from the unenviable task of trying to remove stones and weeds from his barely tillable plot of land. He looms against the horizon, a monumental figure of rural poverty and unending toil, commanding the viewer's respect, however grudgingly that might be given. Not surprisingly, the critical and public reaction was almost universally negative. Regardless of the unfavorable response, it had become evident by the end of 1863 that Millet's work was part of a larger movement toward an art that represented the lives of everyday people, irrespective of their social position, wealth, education, location or appearance. The painters whose work was most noticeable at Salon des refusés that year were similarly committed to portraying contemporary life, and although a number of stylistic vocabularies were employed to that end, the overarching principle signaled a rejection of subjects that did not relate to issues and concerns of modern life.

Millet would continue to develop his vision of rural labor, broadening it to include an increasing number of working farm women engaged in sheep-shearing, tending cattle, gleaning and harvesting the fields as well as teaching the next generation how to knit and spin. All of these themes and ideas would be absorbed and further elucidated by the young artists who first admired Millet's work in the late 1860s and early 1870s, including Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884), Camille Pissaro (1830-1903), Léon-Auguste Lhermitte (1844-1925), and Julien Dupré.

One of Dupré's most successful early paintings, Les Lieurs de gerbes (Binding Sheaves of Wheat), reflects the influence of Millet on his work. (fig. 7)

fig. 7: Julien Dupré, Les Lieurs de gerbes (Binding Sheaves

of Wheat), 1878. Oil on canvas. Musée de Tessé, Le Mans, France

Exhibited at the Salon of 1878, this large

canvas demonstrates Dupré's ability to handle a

complex, multi-figure composition in the accepted manner of the École des Beaux-Arts as well as his

preference for the subject of rural laborers. So too the dimensions of the

canvas-nearly seven feet wide-reference the large scale not only of Millet's Gleaners, but also of Courbet's monumental paintings from the early 1850s.

In the foreground two men reach across the piles of newly harvested wheat as

they bind it into sheaves. Their curved backs and outstretched arms echo the postures

of the women in Millet's Gleaners as does the pose of the

red-scarfed woman in the middle ground stooping over her bundle of wheat. The

standing woman in the foreground is silhouetted against the horizon, a

compositional strategy frequently employed in Millet's canvases.[35] Dupré's

Lieurs

des gerbes, however, was well

received at the Salon. No one suggested that the woman's bright red scarf was a rural equivalent

for the red Phrygian cap of liberty nor did anyone imply that Dupré supported political insurgency. Even with

conservative juries dominating the Salon selections in the mid-1870s, Realism

had become acceptable and the subject of rural life was no longer perceived as

a social or political threat.

Explorations

in style and technique

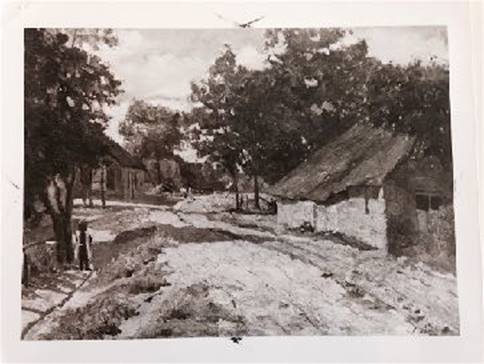

Dupré's initial interest in rural subjects was fostered by Desiré Laugée, his future father-in-law, on trips to Picardy with his friend Georges Laugée. The young artist undoubtedly joined the Laugée family painters in expeditions into the countryside where he observed the rhythms of rural life as well as the various types of work that were involved in farming. Unlike Millet, Dupré was raised in a thoroughly urban environment; agricultural work and rural customs were quite new to him. The undated work entitled Village Scene may illustrate an early attempt at portraying a rural village, perhaps in Picardy. (fig. 8)

fig. 8: Julien Dupré, Village Scene, n.d. Oil on canvas.

In this uncomplicated image of a road leading into a village, Dupré has emphasized texture and light. With loose brushwork reminiscent of the emerging Impressionists, he created a dynamic interplay between bright sunlight and the dark green trees and brown roofs. The small figures strolling along the edge of the road remain undefined, serving to mark the progression of spatial depth almost as if it were an exercise in linear perspective. The attention to light and brilliant color suggests that Dupré visited the independent exhibitions of the Impressionists in Paris, and further that he was exploring some of their techniques. Although Dupré never embraced the broken brushwork of painters like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, he did eventually incorporate looser brushstrokes and the use of the palette knife in order to capture the play of light and texture in his compositions. Most important, Dupré and the Impressionists shared common roots in the Realism of the 1840s and 1850s with its emphasis on depicting contemporary life.

Throughout his career Dupré's work strongly reflected his education in traditional academic art. The École des Beaux-Arts provided students with a solid foundation in drawing and painting, supported by rigorous study of both classical and Renaissance art including classes in history and literature as well as the visual arts. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the École's curriculum was increasingly challenged as artists began to question the primacy of history painting and more importantly, the overwhelming dominance of the school's faculty members as arbiters of public taste, both in the classroom and as members of the annual Salon juries. In addition, the development of photography and the influx of Japanese art and design in the middle of the century tested the École's hegemony of European visual arts.[36] Dupré's Salon debut in 1876 occurred at the height of this conflict, when artists were increasingly hosting their own exhibitions and the independent art dealers of Paris began sponsoring significant exhibitions in their commercial galleries along the rue Laffitte in the 9th arrondissement.[37] For a young artist this presented a chaotic, if exhilarating, environment.

Dupré relied on the techniques he learned at the École des Beaux-Arts to develop his compositions, typically beginning with drawings, then moving on to a small oil sketch followed by the final canvas. Several of his oil sketches still exist and it is clear that this was an important medium in which he could work out the poses of his figures. (fig. 9)

fig. 9: Julien Dupré, La Moisson en Picardie, 1876. Oil sketch. Jérémie Jouan Collection, Paris.

In the early years of

his career, he adhered to this process quite faithfully. By the 1880s, however,

he began to produce gridded drawings of a single figure, which may indicate

that he was using photographs of his models rather than sketching them posed in

the studio. Returning from the Fields (n.d.) and an accompanying drawing

illustrate this process. (figs. 10, 11) The painting is a relatively straightforward

image of a walking figure in a landscape, but the artist has carefully

positioned the figure of the young woman on a gridded paper in order to

transfer it precisely to his canvas. These gridded drawings appear only for a

short period of time, suggesting that the artist may well have experimented

with photography, but eventually decided that it didn't suit him.[38] Nonetheless, this possible use of photography

does reveal Dupré's willingness to consider technical strategies that would not

have been acceptable at the École. As he gained more confidence in his own vision and

skill, he was increasingly open to the exploration of new ideas, styles and

techniques.

fig. 10: La moissoneuse or Returning from fig. 11: Study for Returning from the

Fields,

the Fields. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Graphite on gridded paper

Building on Success: The 1880s

When Dupré received a third class medal at the 1880 Salon, he secured his position as a contributing member of the Paris arts community; and he was awarded the privilege of being included in all future Salons without being required to submit his work to the jury. Knowing that his art would always be accepted not only signaled success as a painter, but also assured his prospects for financial security. In 1881, he further solidified his reputation by winning a second class medal for La récolte des foins, (Harvesting Hay), a painting that effectively sums up the Dupré's work at the time. (fig. 12)

fig. 12: Julien Dupré, La récolte des foins, (Harvesting Hay), 1881. Oil on canvas.

Chimei Culture Foundation, Taiwan

Like his Salon debut

painting, it is a very large (4' 5" x 7' 6") multi-figure composition showcasing rural laborers

harvesting hay. There have been some changes since 1876 however. The figures

are smaller in scale, dwarfed by the massive hay wagon at the center of the

canvas. Five yoked horses wait patiently for the harvester to pitch one last

rake full of hay onto the massive pile before they start the journey to the

farmstead. On the other side of the slightly tilted wagon a single woman holds

the left rear wheel steady with a staff. In the distance cattle graze beside

haystacks while thunder clouds gather overhead. Rather than presenting peaceful

workers in the fields, as in Les Lieurs de gerbes, this image offers the

possibility of a narrative: will the thunderclouds suddenly burst into an

autumnal storm, or worse, will the wagon tip over with the weight of the hay,

harming the woman trying to maintain its equilibrium. The tension involved in

pitching that last sheaf of hay onto the cart before the storm breaks also

reveals Dupré's more intimate knowledge of agricultural labor at this point in

his development.

The 1880s were a

decade of experimentation for Dupré.

He simultaneously expanded his subject matter and investigated new techniques

and compositional strategies. Much of this effort is associated with painting

trips he made to Normandy beginning in 1881-82. Two canvases in particular

offer an opportunity to observe Dupré's gradual shift to a more painterly

technique; both versions of Au pâturage (In the pasture) deal

with the same subject and almost, but not quite, the same composition. The

subject was described by Joseph Uzanne in Figures Contemporaines, tirées de

l'Album Mariani:

His painting, Au Pâturage, which was exhibited at the Salon of 1882, depicts a large peasant woman pulling with all her might on a rope that a cow with a superb coat is dragging in spite of all of her efforts, is now in Saint Louis. This work, popularized by the engraving, was noticed by the critics because of the line. Not since the steers of Constant Troyon or the superb flocks of Charles Jacque, has a work depicted to such a degree the luxuriant force of the animals and their calm and natural beauty.[39]

In these images, Dupré again includes a narrative element that invites speculation from the viewer. (figs. 13, 14)[1] Has the cow pulled loose from the tether or is it simply resisting being leashed in the first place; and will the cowherd succeed in directing her charge to the desired goal? By encouraging the audience to propose their own interpretation of what's actually happening on the canvas, Dupré succeeds in engaging them in the painting itself. And for urban art lovers, the unfamiliarity of the scene may well have made it even more appealing.

fig. 13: Au pâturage (In the pasture), 1882. Oil on canvas. Mildred Lane Kemper

Art Museum, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri

fig. 14: Julien Dupré, Au pâturage (In the pasture), 1883. Oil on canvas. University of Kentucky

Art Museum, Lexington, Kentucky

A closer look at the paintings discloses changes in Dupré's formal methodology. The 1882 painting is very much in the style of his previous works, focused on "line" as Uzanne noted in the Album Mariani biography. In contrast, the 1883 canvas shows looser brushwork and the use of a palette knife. Equally important is the shift in he spatial organization of the landscape. In the earlier work, the background hillside seems relatively close to the pasture and the stream. In the later painting the artist has opened up a long scenic vista of smokey blue hills and another distant pasture where a herd of cows graze. By shifting to a slightly different perspective, Dupré suggests not just a single farmstead, but the presence of neighboring farms as well, thus adding another potential element to the narrative. Likewise, the much admired "superb coat" of the 1882 cow gives way to a more realistic-and substantially muddier-treatment in the later painting.[40]

The grandest of these narrative paintings is Le Ballon (The Balloon), Dupré's entry for the 1886 Salon. (fig. 15) The very large canvas (8' x 6') introduces a group of farm workers pausing from their labors to watch a hot air balloon drift across the sky above them. Although the figures all turn away from the viewer, the audience instinctively looks up at the sky along with them. The automatic response of looking up immediately involves the viewer in the unfolding story of the balloon's progression above the landscape, and because the figures are nearly life-size, the sense of being part of the scene is quite convincing. With considerable sophistication Dupré demonstrates his understanding of human nature and his delight in sharing the unexpected joys of daily life.

fig. 15: Le Ballon (The Balloon) 1886. Oil on canvas. Reading

Public Museum, Reading, Pennsylvania

An

International Artist

By the end of the decade, Dupré had established an international reputation, beginning with his relationship with M. Knoedler & Co. in New York and the Arthur Tooth & Sons Galleries in London in 1879. In 1881 Blakeslee Galleries of New York also began purchasing Dupré's work and soon became the painter's primary gallery in the United States, where his paintings were very popular with American art collectors. Given his success in the US, it was not a surprise that Dupré's first international exposition was the 1887 Interstate Industrial Exposition in Chicago. This annual event was originally intended to spotlight the recovery of Chicago after the Great Fire of 1871; W. W. Boyington's newly designed building contained space for over 300 exhibitors in addition to a 2400 square foot gallery for the fine art exhibition. Although originally focused on American artists, the exhibitions quickly became more international under the curatorial direction of Sara Hallowell, whose official title of "secretary" belied her key role in educating and guiding the development of significant art collections in the city.[41] The 1887 art exhibit contained over 100 paintings from the collection of George Seney (1826-1893), then president of the Metropolitan Bank of New York and the new owner of Dupré's 1886 Salon painting, Le Ballon. All together, there were 483 works of art on display, representing the US as well as France, England, Holland, Italy and Germany. The older generation of painters associated with Barbizon were represented by Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Camille Corot, and Théodore Rousseau, all of them deceased. The younger generation included Rosa Bonheur, Jules Breton, Jean-Charles Cazin, P.A.J. Dagnan-Bouveret, Alfred Stevens and James Tissot.[42] And of course Julien Dupré whose entry was Cattle at Pasture, owned by M. Knoedler & Co.[43] Unfortunately, the title does not provide any clue about which painting of "cattle at pasture" this might have been.

The

next American exhibition to include Dupré's work was in Minneapolis, Minnesota in

1890. It too hosted both industrial and

artistic sections, and like the Chicago Exposition of 1887, the size and scope

of the works on view was remarkable. William M. Regan, General Manager of the

Exposition, was pleased to report that on hearing "of a rare collection of

paintings at Aix-la-Chapelle, Germany, I hastened there to investigate."[44] Within three weeks, he had

successfully negotiated the loan of a collection of old master

paintings-including works by Antony Van Dyke, Peter Paul Rubens and Titian-to

be sent to Minnesota for the exhibition. In seeking out contemporary art Regan

persuaded Hendrik and Sientje Mesdag from The Hague to part with over thirty of

their own paintings and he also obtained a selection of French, British and

American paintings.[45] Dupré was represented by two canvases, Milking

Time and Retuning from the Market.

Back in Chicago three years later, Dupré's work was on display at the ground-breaking World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. One of the largest and most spectacular of the world fairs of the nineteenth century, it was designed by a consortium of Chicago and New York architectural firms in the Beaux-Arts style taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It was here that the Ferris Wheel was introduced as well as a multitude of other inventions such as alternating electrical current, the zipper, moving walkways and Cracker Jack.[46] Dupré's contribution, a painting of a milkmaid near the Durdent River in Normandy, was part of a vast exhibition held at the Palace of Fine Arts. It was listed as #442, Valley of the Durdent.[47] Many of these international expositions were overwhelming in scale and scope, offering artists in every media a prestigious credential, but perhaps not quite as much opportunity in terms of sales.

French

contemporary art was again well represented in the fall of 1898 when Dupré's

work was on display at two international expositions in the midwestern US, one

in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and one in Omaha, Nebraska. Fortunately, the art

journal, Brush and Pencil, reported on the Milwaukee Industrial

Exposition and included a photographic illustration of Dupré's painting, Milking

Time. (fig. 16)

fig. 16: Julien Dupré, Milking Time, n.d.

Author James William Pattison had quite a lot to say in his review. He began by setting up an argument about the relative merits of "ideality" and "roughness" in a comparison of paintings by William Bouguereau and Dupré. Pattison concedes that "Bouguereau can paint" and cites his technical skill as the most important aspect of his work.

It is "slick" of course, and the flesh is only ideal flesh, but it charms a host of people who love to see paint smooth. If you do not like this, pray look at something else. There is rugged food in No. 39, by Julien Dupré. It is a picture of dimensions, the cow in it not small; and what a black in that nearest one! The cattle are grouped in a shadowed foreground, and beyond them sweeps a streak of sunshine, athwart the plain, real sunlight too. It is cool in color and boldly, freshly brushed, a good example and a delightful picture. Too rough, is it? Then turn around and look at the other Bouguereau-something to please every one here. Possibly this one is a shade less important than the larger canvas mentioned. [He is referring to another Bouguereau painting in the exhibit] But this little girl, in white waist, silver blue petticoat and bare legs, hanging over the wall is very charming to the people who are looking at it, and surely the people have rights. Suppose I do like the Dupré better?[48]

The exhibition was curated by Henry Reinhardt of Roebel & Reinhardt, who had galleries in Chicago, New York and Paris, thus facilitating the process of selecting and obtaining art for the Milwaukee Industrial Exposition. There was probably also a project office in Milwaukee to coordinate the logistical arrangements for the exhibit.

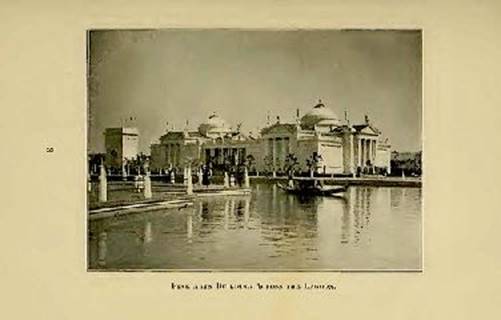

Further west, the city of Omaha, Nebraska hosted the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. (fig. 17) The Fine Arts Building was designed in the same Beaux-Arts style as the Worlds Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Nicknamed the White City because of its use of electricity to light the fairgrounds at night, the Chicago fair established an architectural vocabulary that quickly became standard for public buildings throughout the US. Although smaller than the Chicago exposition, the Trans-Mississippi fair was no less international, as evidenced by the extraordinary art exhibition with works from throughout Europe as well as the US.

fig. 17: Fine Arts Building at the

Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, Omaha, Nebraska 1898.

Dupré's

contribution included two paintings, The Herder and In the Pasture, which

was loaned by the St. Louis Museum of Art.[49]

(See fig. 13) The

work was well received by the Omaha press. Ethel Evans, a reporter for the Omaha

Daily Bee, discussed In the Pasture at length.

He [Dupré] is content in depicting a peasant woman watching her cows drink from the tubful of water, with sheep browsing near by-a commentary on the quiet peaceful life of the country woman. Or he represents her at her busy hour-The Milking Time-a picture exhibited here several years ago, and which most of us remember with pleasure. In No. 144 [n the Pasture] he shows what a master he is of the anatomy of the cow. The picture depicts a conflict between the cow, in her efforts for freedom and her mistress' will. The peasant woman has just driven in the tether-stick with the maul, which always lies in the pasture for that purpose; she is about to leave the cow to graze there, when in its longing to join some cattle in the middle distance, it breaks the tether. She grasps the broken rope and with the full weight of her body braced backward she pulls in one direction, while the cow strides on. This is not a drawing-room animal like the sleek creature of William Howe-No. 267-it is shaggy and dirty, strong and natural. It is difficult matter enough to paint the figure of a woman in such violent action, but as a cow will not pose, it is necessary that the painter should be a master of the anatomy to represent so forcibly its movement. The whole composition is interesting. In the distance a cottage with smoking chimney nestles among the trees; in the middle distance some cattle are comfortably lying in the pasture, through which flows a little stream. In the foreground the peasant in her wooden shoes struggles with the cow. While the picture is not vibrating with the light which many painters make the first object and many critics demand as the first requisite of a good picture, it is atmospheric, the drawing is masterly, incomparably firm and the general impression quite of the first order. Others may have greater ingenuity and subtlety and have carried qualities of execution much further, but Dupré observes the character, both human and animal, with an unfailing truthfulness and shows quiet good taste in the arrangement of his simple subjects.[50]

This commentary is quite similar to that of James William Pattison in his review of Dupré's work at the Milwaukee Industrial Exposition. Both reporters demonstrate an awareness of contemporary debates within the French art world, and both find praiseworthy qualities in Dupré's work based on his adherence to a naturalist aesthetic that is neither "slick" nor overly avant-garde. Most of all, they express an appreciation for his choice of subject matter showing the daily life of ordinary people.

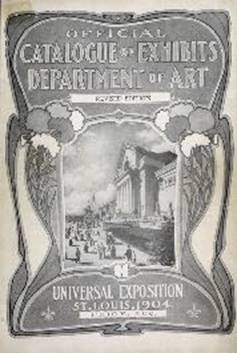

In 1904 the city of St. Louis hosted the last of the grand world fairs before the onset of World War I. The ostensible purpose was to celebrate the centenary of the Louisiana Purchase and the beginning of the expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who headed west on the Missouri River in the spring of 1804. In reality, it was an extravaganza on a monumental, if somewhat chaotic, scale.[51] Architect Cass Gilbert was commissioned to design the Fine Art Palace at the top of an imposing hill in Forest Park.[52] Like the Beaux-Arts architecture of the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the style of the St. Louis fair was grandiose, extraordinarily ornate-and very popular. Halsey Ives, who had organized the art exhibition at the Chicago fair, was asked to take on the leadership of the Department of Art for St. Louis a decade later. As the first director of the St. Louis Art Museum, which opened in 1881, Ives was well suited to the task.[53] He also seems to have admired Dupré's work, having purchased Faneux chargeant une brouette (Haymakers loading a wheelbarrow) in 1882 for his personal collection.[54]

Dupré had three paintings on display at the St. Louis fair, unlike the majority of other artists who had only two works in the exhibition. (fig. 18)

fig.18: Official Catalogue of Exhibits,

Department of Art, Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, Missouri, 1904.

The catalogue entry noted that he received a silver medal at the 1889 Exposition universelle in Paris and that he had become a chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 1892. The works on display were The Return of the Herd, Evening, and Near a Pool.[55] The work titled Evening may well have been the artist's Salon entry for 1902, entitled A la fin du jour (At the end of the day); and Return of the Herd is probably the painting of the same title in French, Retour du troupeau, completed in 1903.[56] The presence of Dupré's work at so many of these international expositions in the US speaks not only of his popularity with American art patrons, but also of the confidence that his dealers had in his work. Blakeslee Galleries in New York handled a great number of his paintings, but he was also represented by Knoedler & Co. and Boussod, Valadon & Co., both of whom had galleries in Paris and New York.

European

developments

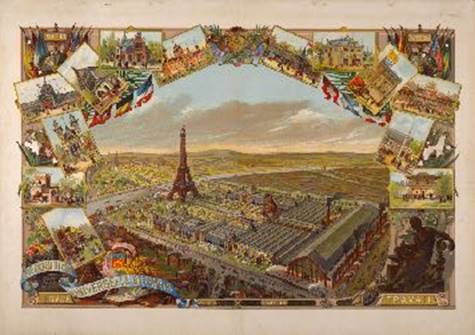

The French international expositions in 1889 and 1900 were particularly important for the arts. The 1889 Expo marked not only the centenary of the French Revolution, but also signaled the nation's return to a position of democratic leadership in the wake of the destruction caused by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and the fall of the Second Empire. (fig. 19)

fig. 19: General view of the Exposition universelle of 1889.

Engraving. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

With the Eiffel Tower as its signature element, the fair was intended to be a declaration of industrial prowess, financial stability and cultural sophistication. The Palais des Beaux-arts, designed by Joseph Bouvard, stood immediately to the north of La Tour while the Palais des arts libéraux occupied the same position to the south; these prime locations adjacent to the centerpiece of the entire Exposition articulated the importance of the fine arts and the liberal arts in France's vision of itself.[57]

The large Palais des Beaux-arts included exhibitions from across the globe, with 1,632 paintings from France alone. Dupré had seven paintings in the galleries, five of them from museums in New York, St. Louis, Glasgow and Paris, plus his Salon painting from 1888, L'heure de la traite, (Milking Time) and one other painting, La Fenaison (The Hay Harvest).[58] He was awarded a silver medal at the Exposition, an honor that recognized his body of work and affirmed his importance as a cultural leader. Two years later, in 1892, he would become a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur.

The decade of the 1890s opened with much praise for Dupré's Salon entry, La vâche blanche (The White Cow) and what appears to be the first published notice of his oeuvre in general. (fig. 20)

fig. 20: Julien Dupré, La vâche blanche (The White Cow), 1890. Oil on canvas. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

It appeared in a British journal, The Magazine of Art, in 1891. Author M. H. Spielmann opens with a statement confirming Dupré's role in France: Julien Dupré is one of the most rising artists of the French school He is individual in his work, accurate as an observer, earnest as a painter, healthy in his instincts, and intensely artistic in his impressions and in his translation of them. Adding to this a subtle sense of tone and colour, a natural feeling, so to speak, for chiaroscuro, and facility for composition, he is always one of the attractions in every Salon exhibition. Yet he is still a comparatively young man.[59]

This is followed by a discussion of La vâche blanche as an exemplar of the painter's merits. "The cow-taking a patient and intelligent interest in the operation of milking-is superbly drawn, and her expression admirably rendered. The light and shade, the balance of the composition, and the rendering and disposition of the figures combine in this picture to produce a canvas which pleases the spectator the more he examines it."[60] What makes this commentary especially worthy of note is that the author was the editor of The Magazine of Art and one of the leading art critics in London at the time. He was a well informed and astute observer who championed open debate by proponents of many different aesthetic perspectives.[61]

In these years, Dupré expanded his scope within Europe as well as continuing to

be an active contributor to the American and British art market; he also

maintained a regular teaching practice at the Académie Montparnasse.[62] Throughout his career,

Dupré regularly submitted paintings to the Paris Salon as well as the annual

salon in Saint-Quentin near his wife's family home. In the 1890s, however, his

work appears somewhat unexpectedly in salons and special exhibitions in central

Europe. The first occurrence was the international exhibition held in Munich in

1890 where Dupré received a gold medal for his painting, Hay Harvest.[63] Why he decided to

exhibit in Munich is a matter of conjecture. He may have been persuaded by a

colleague who had contacts in that city, or perhaps one of his dealers

suggested it would be a good opportunity to expand his market. The city of

Munich was unusual among German-speaking communities in its commitment to

holding international exhibitions every ten years. The goal was not only to

refresh the local arts community by inviting foreign artists to participate,

but also to focus attention on the cultural environment in the city itself. In

Paris, this undoubtedly seemed like an opportunity to generate enthusiasm for

contemporary art in Europe. To the artists of Munich, however, it was a rationale that only fostered

discontent. The comparison between the environment that they worked in and that

of the foreign artists only highlighted how restrictive their city had become.[64] Just two years later, the

first of the Secessionist groups would emerge in Munich.

Dupré found a more congenial environment in 1895 when his work was shown in the annual exhibition of Bohemian artists in Prague. How he became involved with this group remains unknown, but his painting, In the Fields, was featured with a full-page photographic reproduction in the exhibition catalogue.[65] (fig. 21) As it happened, the painting was so well received that it was purchased immediately by what is today the National Gallery of Prague.

fig. 21: Julien Dupré, In the Fields, 1895. Oil on canvas. National Gallery

Prague.

III. Dupré

Studies

Redefiniing the Context

Throughout his career, Julien Dupré maintained a reputation as an artist of merit and integrity. For thirty-five years, he never once failed to submit his work to the annual Salon of the Socitété des Artistes Français, and his efforts were recognized with a number of medals and honors. In addition, he formed productive relationships with a number of art dealers who represented his work both in France and abroad. His work received international recognition as well as ample attention from private collectors, the result of which was a comfortable degree of financial security. In his personal life, he was apparently happily married and generally untroubled by family discord. In short, he was a successful professional painter, committed to his art and aspiring to create redoubtable paintings without engaging in unnecessarily theatrical behavior. It may be, however, that Dupré's choice to pursue his career within accepted social structures-and without excessive public fanfare-has overshadowed his contributions to the history of art.

Dupré's oeuvre has long been appreciated, but rarely studied. He has been characterized as an animalier, a student of Jules Breton, and repeatedly as the nephew of Jules Dupré. To set the record straight, Dupré was never a student of Jules Breton and, in fact, the two painters approached their work from quite different perspectives. Breton's sentimental images of rural life are essentially a continuation of an eighteenth-century genre tradition, influenced by nineteenth-century Realism, but far less grounded in its social themes and aesthetic ideas than Dupré's work.

The conflation of Jules and Julien Dupré, however, is a more serious issue. Even Vincent van Gogh thought that Julien was related to Jules, asking parenthetically in a letter to his brother Théo "(is this a son of Jules Dupré???)".[66] Kudos are due the Dutch artist for asking a question about it rather than assuming a relationship based solely on a common surname. Others have not been so thoughtful, but simply presumed a relationship-usually cited as that of uncle and nephew-and repeated the falsehood in auction catalogues, journal articles and sales sheets. The fact is that there is no relationship between the painters whatsoever.[67]

The problem persists even today, reinforcing an uncertainty about who Julien Dupré was and when he worked.[68] Paintings are often incorrectly attributed, typically with the work of Jules being assigned to Julien, thus obfuscating the work of both artists. One result of that particular error has been the categorization of Julien as a Barbizon painter, and while it is true that he was a beneficiary of the Barbizon painters' work, he was not a practicing artist until the 1870s. Further, the Barbizon artist he is most closely aligned with is Millet, not the landscape painter Jules Dupré.

The description of Dupré as an animalier is a more complex subject stemming from his presumed association with Barbizon and the incomplete definition of his work that exists as a consequence of that misunderstanding. Without reservation, his oeuvre includes many canvases featuring domesticated farm animals, but Dupré is not an animal painter in the tradition of the Dutch master Paulus Potter (1625-1654) or Constant Troyon (1810-1865) who was associated with Barbizon. Both of these artists preferred to paint animals rather than people, and even when humans appeared in their compositions, they tended to be small figures playing a secondary role. With few exceptions, Dupré's canvases feature human beings as the central focus of his compositions.

The emphasis on Dupré's depiction of animals-particularly cattle-emerged most prominently when he began to paint milkmaids in the late 1880s. These images were widely reproduced in both Europe and the US because of their popular appeal. By the turn of the century, Dupré's reputation as an animalier was deeply entrenched, and has remained so into the twenty-first century. It is a critically incomplete description of his work that deserves to be amended to more accurately reflect the totality of his production.

Milking

Time

Up until the late 1880s, Dupré's subjects were primarily rural laborers-working in the fields, enjoying a brief respite from their toil, tending cattle or sheep, or feeding poultry in a farmyard. In 1888, however, he began to paint milkmaids. The first iteration was La porteur de lait, which was sold to Boussod & Valadon early in the year.[69] The second was a Salon painting L'heure de la traite (Milking Time), and the third was a réduction or copy of the Salon painting.[70] The two versions of the Salon painting, today in the St. Louis Museum of Art and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, are identical scenes with different landscape backgrounds. In the following years, paintings of milkmaids proliferated. Obviously, these types of images were popular, which is always an incentive to produce as many as the market can absorb, but there remains the question of why milkmaids suddenly appear in Dupré's work and why these images were so appealing to the art buying public.

Millet was Dupré's

most immediate predecessor for images of milkmaids. Over the course of three decades,

he had often treated the subject and his work was clearly one of Dupré's

sources of inspiration. Art historian Robert Herbert focused on Millet's

milkmaids in a 1980 article, noting that Millet's milkmaids are visually linked

to Normandy by their costumes, and even more specifically by the copper milk

jugs that they carry on their shoulders.[71]

Dupré was undoubtedly aware of Millet's images, perhaps from the posthumous

studio sale of his work in 1875, but almost certainly from the retrospective

memorial exhibition at the École des Beaux-arts in 1887. Art historian Maura

Coughlin added another element for consideration in her discussion of the

milkmaid as a popular tourist trope. "The milkmaid is an icon of French popular

culture that has long signified the region of Normandy both to outsiders and to

Normans. This female figure appeared frequently in early nineteenth-century

travel literature and popular art, and can still be found today. Her iconic

status is demonstrated by the history of Arthur Le Duc's bronze sculpture Norman

Milkmaid, first shown at the Salon of 1887."[72]

By 1888, images of milkmaids were on display in both specialized art

exhibitions and in popular culture. It may be that Dupré conceived his Salon

painting of L'heure de la traite as a tribute to Millet, whose work was

being so belatedly recognized.

Nonetheless, Dupré does not paint the traditional milkmaid associated with Normandy, even though he often painted on site there. His milkmaids are dressed in the well worn garb of everyday farm workers and they carry the tin milking pails that were still in use well into the twentieth century. Further, the pails are often suspended from a yoke worn over both shoulders. The image of a milkmaid balancing a copper jug over one should by attaching it to single strap does not appear in his work, perhaps because that was no longer a common method of carrying milk in Normandy. (fig. 22)

fig. 22: Julien Dupré, Laitiere (Milkmaid) n.d. Oil on canvas.

Just as in his images of harvesting or tending livestock, Dupré does not shy away from depicting the grubbiness of milking cows or the difficulty of transporting the milk to the barns. Nor are his models pretty girls posing in costumes with strategically placed rips and tears. They are physically strong and hard-working, grounded in a life of seasonal cycles rather than industrial production quotas. Seen in that context, they offer a glimpse of a life of honest and healthy work. For a culture growing weary of its own restrictive behavioral conventions and increasingly conscious that the class systems of the past were dysfunctional, these visual reminders of a life based on less convoluted social structures must have been quite attractive.

History

painting in the fields

Dupré's choice of large scale Salon canvases carried an implicit challenge to the longstanding premise that history painting was defined, in part, mandating that subject matter be restricted only to historical, classical or biblical events. History painting was placed at the top of a hierarchy that categorized different types of painting according to preconceived notions of importance. In contrast, genre painting, which would have typically included rural scenes of peasants and country life, was considered one of the least important subjects. This system was endorsed by the French Academy, not only for the visual arts but for the literary and dramatic arts as well. Challenging that order was considered heretical in the middle of the nineteenth century when Courbet exhibited A Burial at Ornans, a twenty-foot long painting depicting an ordinary funeral in a small provincial town. The sheer size of the canvas proclaimed that daily life was deserving of treatment on the same scale as history painting. By the time Dupré began to exhibit at the Salon in 1876, the use of such large-format paintings had decreased in every category except traditional history painting. The causes of this were as much practical as political; the Franco-Prussian War had ruined the French economy, and it was prohibitively expensive to develop a truly large painting.

Most of the post-war generation of young painters were far from wealthy, which makes Dupré's foray into large-format canvases in the late 1870s quite unexpected. He was not wealthy and he had a family to support, but by 1879 when he painted Le regain, he was just beginning to enjoy a number of sales of his more modestly sized works. Le regain (40 x 50 inches) was followed in 1881 by the larger La récolte des foins at 48 x 88 inches (4' x 7.5'); (see fig. 12) and in 1883, Le Berger measured 55.5 x 78.5 inches (4.5' x 6.5'). Le Ballon, painted in 1886, was the largest canvas of all at 96 x 78 inches (8' x 6') (see fig. 15) All of these paintings feature rural workers, whether harvesters or shepherds, unapologetically portraying contemporary life on a grand scale rather than historical, classical or biblical subjects.

The only other artist working on this scale was Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884), who began to experiment with large-format images of rural scenes at about the same time that Dupré did. Bastien-Lepage had previously developed two large history paintings on standard classical and religious subjects, but in 1877 he began compose a large canvas entitled Les Foins (Haymaking) that measured 71 x 72 inches (approximately 6' square). It was exhibited at the Salon of 1878 where Dupré certainly would have seen it just as Bastien-Lepage would have seen La récolte des foins and Le Berger.[73] (fig. 23)

fig. 23: Jules

Bastien-Lepage, Les foins (Haymaking), 1877 (Salon of 1878). Oil on canvas. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Both men were indebted

to the work of Millet, but their interest in portraying rural subjects as if

they were contemporary history painting sets them apart. They undoubtedly knew

each other, but there is no evidence to date that they were more than

professional acquaintances. Bastien-Lepage went on to produce other large scale

images such as Potato Gatherers shown at the Salon of 1879, and The

Wood Gatherer, a very large canvas, for the Salon of 1882. He soon

emerged as a leader of the Naturalist movement then flourishing as an

alternative to both Impressionism and traditional academic art-or more

accurately, as a blending of the merits of both methodologies.

Reporting on Dupré's work two years after Bastien-Lepage's premature death in 1884, journalist Sophia Beale saw a definite relationship between their work.

In La Prairie Normande, by M[onsieur] J. Dupré, we have another type of everyday life. A vigorous peasant-girl, such as one sees in every part of France, dressed simply and picturesquely, her hair bound up in a coloured handkerchief, and her feet shod in sabots, is dragging her cows home to be milked. The cattle are well drawn, and the action of the girl is good; but her face might have been less plain, without ceasing to belong to the type of a 'femme du peuple'. These younger Frenchmen, following in the train of Bastien-Lepage and Le Rolle, rather revel in their love of what is ugly; but surely there is a medium between sentimentality and unreality, and positive ugliness.[74]

Although Beale did

not realize that Dupré and Bastien-Lepage began exploring similar Naturalist

ideas at the same time, she perceptively acknowledged their mutual commitment

to the depiction of unfiltered realism. Other painters would soon follow their

example, among them Léon Lhermitte, George Clausen and Albert Edelfelt.[75]

Although Beale found Dupré's work a little too plain and perhaps too socially aware to be entirely comfortable, these are the qualities that characterize his oeuvre and distinguish it from the Naturalist artists who preferred to avoid the reality of rural work in favor of a prettified and tidy scene. Dupré's harvesters are tired and thirsty and hot; their clothing is patched and worn; the hay wagons are a bit rickety and the sheep and cows are whole-heartedly muddy. The women and men alike are well-muscled, though not always attractive workers. Even the milkmaid paintings, which are unquestionably the most sentimentalized of Dupré's work, are not sanitized. They remain grounded in the life of the agricultural laborers of Picardy and Normandy, and they offer a more enduring snapshot of a rural way of life that would disappear within a few years as the industrialized machines of war rolled over the very same fields that Dupré painted.

A

Symbolist Mood

By the turn of the century, Dupré had become one of the leaders of the French art establishment. Together with Léon Bonnat, William Bouguereau, Jean Léon Gérôme, Jean-Jacques Henner and Jehan Georges Vibert among others, he served on the jury for the Salon, but unlike some of his colleagues, Dupré continued to explore new directions in his work. These changes were already discernible in the four paintings that he exhibited at the Exposition universelle in 1900. In Vâches a l'ombre (1898) and La Vallée de la Durdent (1896), the artist's interest in sharp contrasts of light is increasingly evident. Rather than spotlight the foreground of these paintings, Dupré has created bursts of light in the background, shrouding the cows beneath the trees as they gaze placidly at the viewer, creating a sense of a breezy summer day. Similarly, in Chemin au Mesnil (1891) the village road is dominated by cows and sheep lumbering through patches of sunlight on their own. The slightly later Berger et son troupe (1896) depicts a shepherd watching his flock graze on the shaded roadside grass while in the middle ground behind them is a patch of brilliant light throwing the trees and sky into high relief. (fig. 24)

fig. 24: Julien Dupré, Berger et son troupeau, 1896 Oil on canvas. Private collection

In each of these paintings, Dupré elicits a reaction to a particular tableau of country life, directing the viewer's gaze to the brightly lit areas of the canvas in the middle of the composition, in essence requesting that the audience conceptually step beyond the shadowed foreground and into the sunny landscape at the heart of the image. There, the viewer can imagine himself as part of the scene. This strategy marks a departure from Dupré's earlier narrative approach in which the artist encouraged observers to devise a story about the action shown on the canvas. These later works are instead invitations to participate in a scene, to enjoy a specific atmosphere and mood.

The emphasis on mood is most evident in Dupré's single figure compositions of women in the fields. Images of a woman pausing from her work is characteristic of his oeuvre beginning in the 1880s, but over time these figures become enigmatic and isolated. Une bergere et moutons (1902) exemplifies this trend. (fig. 25)

fig. 25: Julien Dupré, Une bergere et moutons, 1902, Oil on canvas.

To

the left of the canvas stands a shepherdess, partly cloaked in shadow as if to

suggest that the sunlit clouds and meadows in the distance are actually the

focus of the painting. The blue of her cloak blends into the blue shadows of

the hills as she silently stands watch over her flock. Her attention, however,

is directed beyond the boundaries of the canvas-off stage in fact. The viewer

cannot tell whether she is musing on some personal concern or simply entranced

with the beauty of the surrounding landscape. This is a departure from earlier

compositions in which the woman shades her eyes with her arm as she looks for

someone in the distance; that simple gesture allows the viewer to develop a

story about who or what she is waiting to see. When Dupré removes this gesture

from his composition, the narrative possibilities disappear, emphasizing

instead the solitude of the individual isolated in a landscape devoid of other

people.